Despite Quetzalcoatl’s ingenious campaign to prevent us from seeing the Rivera murals in the Palacio Nacional — he leagues with Tlaloc, the god of water, to bring a chill wind and heavy rains upon his flock this morning — we brave the elements and load into our taxi so we can arrive at the ticket booth in time to get tickets for today. Cynthia and Debra want cafe and hot chocolate so the cabbie stops at a street-side vendor; we load up, and are singing in the rain under the ticket building’s overhang right next to a mother and daughter who had beat us to the head of the line.

The rain does not relent but other people come and the line soon stretches down the block. At a tad after 10 A.M. we must relinquish bags and ID and some personal information to get tickets and line up in the order our names are called in our group of 20 people before we walk out of the ticket place, down and across the street, and through the heavily guarded security station in the Palacio’s entrance. Biiiiiigggg place. You may not take photos of the left side because government officials might be there and their privacy and safety must be preserved. Our guide takes us up wide stone stairs and around half the building — passing the doorway that Benito Juarez, as Minister of Justice before he became President, used in 1857 to reach the balcony where he announced Mexico’s new, liberal constitution to cheering masses in the Zocalo below — to stand in front of Rivera’s principal and first mural (1929 – 1935).

Personal thoughts for a moment: This floor of murals on three long walls was painted by Rivera during a span of 25 years, ending in 1954. The changes — emotional, intellectual, economic, social, scientific, artistic, political, you name it — through which he lived and felt during that … shall we say turbulent period? … were … you must find your own word for the breadth and intensity of them and the ways they must have affected him as he muraled his way into world history.

“From the Conquest to 1930” is the first mural in his “History of Mexico” series in the Palacio. It’s on three walls within five arches and is most properly read both from right to left and bottom to top. What’s in its three-part allegorical vision of his country’s history? Not much: Woven together visually and conceptually, the Rise and fall of the Aztecs, Spanish conquest, fight for independence from Spain, Mexican-American War, Mexican revolution, the future as a worker’s paradise and maybe 30 other themes and events.

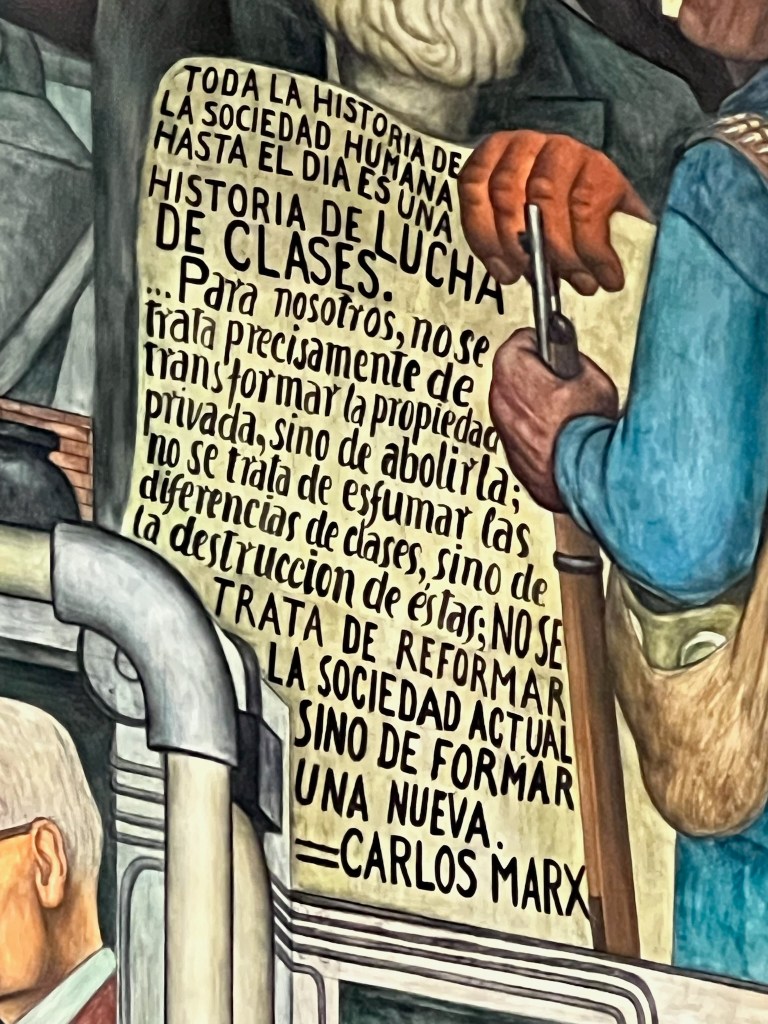

Who’s in it? Quetzalcoatl, Porfirio Diaz, Benito Juarez, Emiliano Zapata, Miguel Hidalgo, Karl Marx, Frida Kahlo and her sister, the Mexican eagle, “negative social forces” and “workers oppressed by police”, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and several casts of unnamed symbolic farmers and soldiers and teachers and priests and politicians, corrupt and otherwise. You could look at this enormous mural for two hours and still know you’ve missed a myriad of themes and connections and concepts. To say, “It’s really good” sums, maybe, all we can say.

Depending how you count, there are another 11 monumental murals of such scenes as “Tlatelolco’s Market View,” “What the World Owes to Mexico,” “The Arrival of Hernan Cortez in Veracruz”. Our guide does not give completely short shrift to explaining elements of each mural, but we were allowed at most two hours inside, dogged by a few soldiers with guns to make sure we do not dally too long.

Huitzilopochtli, the sun god, chases away Tlaloc, and we summon an uber for a $35 hour-long ride to the Sabado Bazar in the city’s rather ritzy San Angel neighborhood. We have a nice lunch in a tapas restaurant whose waiter inexplicably gives us non-tapas menus. We walk around the indoor and outdoor spaces of the rather upscale market, finding, among other nice oddities, a spice store that sells boxes of assorted additives for gin drinks. We limit ourselves to several. And summon another uber for another long ride — distance in Ciuidad Mexico is meaningless — to the museum designed and commissioned by Rivera to house his personal collection of pre-colombian art: the Anahuacalli Museo in the San Pablo de Tepetlapa neighborhood of the Coyoacan barrio. Rivera, BTW, consulted with Frank Lloyd Wright regarding use of local materials for construction.

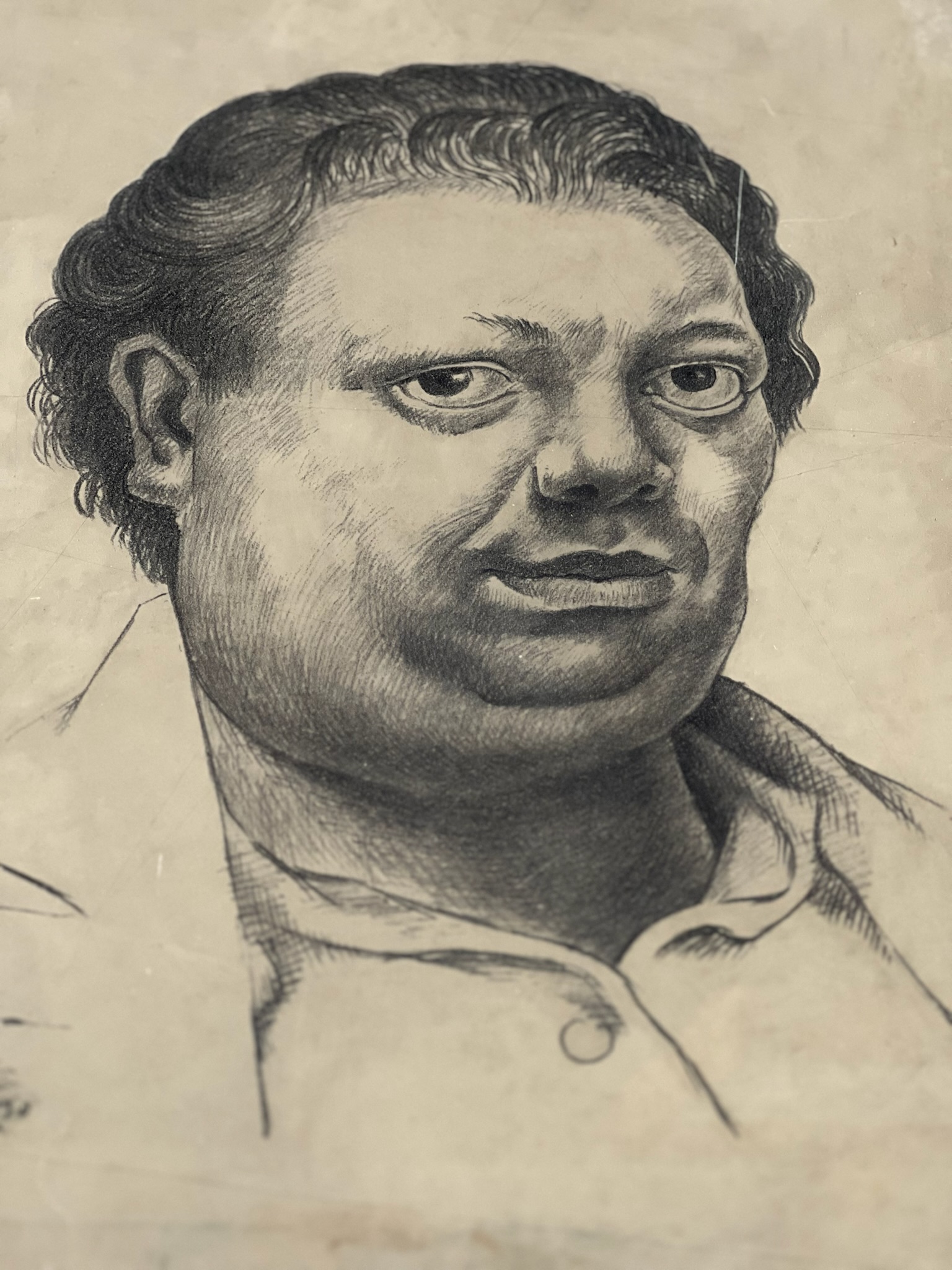

Most rooms on the four floors are very dark with arrestingly illuminated exhibits of numerous small figures of people or gods, the ceilings tiled and painted with designs by Rivera, and connecting walkways hung with modern, abstract “Fantasmas” by the sculptor Wyatt Kahn. With the exception of one monumental room in the center of museum that houses Rivera’s huge “practices” for the National Palace’s main mural and a self-portrait, the rooms are deeply intimate. Zero signage. A very cool place.

We uber another 45 minutes for dinner at the Corazon de Maguey restaurant — “heart of the Maguey” (yucca and/or agave) and our chance to sample the true, traditional dishes of mesoamerican cuisine with rich mole sauces and bizarre ingredients and a flight of three different mezcals (three each with different mezcal plant varieties and fermentation techniques from three different regions … whew). We enjoy it all and wait for our uber outside in the Jardim Centenario while David takes photos of lovers on the park benches.

Our last full day in greater Mexico City. It has been an exciting, frustrating, informative, non-stop, 18,000-step-a-day, multi-layered sojourn with 22 million people to keep us immediate company. And some cars.

One response to “February 17 Mexico City”

Thank you so much for taking this trip so I don’t have to. Your colorful and informative commentary and arresting photos take me there. Clink, clink.

LikeLike