We wake to drizzling rain and the 7-minute walk uphill to the Oporto train station where we hope to revise our tickets for Aviero and Coimbra so we can skip Aviero — scenic seaside canals that would be lovely were the weather even 10 percent nicer — and get to Coimbra earlier in the day so we can see a museum that is open today but closed the rest of our Coimbra time. No dice. Earlier trains to or through Aviero are unavailable or booked. So, we train to Aviero and sit and wait for two hours, then, still under miserable weather, climb aboard our train for Coimbra. NOT! Cynthia slips trying to hoist her heavy suitcase above the two 14-inch aluminum stairs between the platform and train, and sprawls across the train car’s loading area.

We get to Coimbra and the weather, mercifully, has broken, as has some of Cynthia’s skin under her pants, which remained unscathed. We walk along the riverfront hopeful we will find our hotel, following Google maps wicked sense of humor, perform a complicated u-turn within the city and return to our hotel, which was half a block in plain sight from the train station exit. Thank you again, Google maps. Fortunately, our room is ready and we deposit our bags and head straight uphill for the museum.

No, of course, we don’t. Cynthia needs to investigate a way we may be able to take a scenic little electric trolly for free uphill, instead of climbing. So we walk along the riverfront to the Largo da Portagem, a nice plaza with a statue of Joachim Antonio de Aguiar, who shut down Coimbra’s monasteries and convents in 1834. He also made it extremely difficult to find the electric trolly, so Cynthia finds the town’s premier confectionary shop where she fuels up for the climb at a table surrounded by tourists like ourselves.

We find the way to climb to the Castro Museum, which is near the university perched at the top of the steep hill overlooking the old part of the small city. Lovely climb actually: pass a life-size bronze of a seated shoeless woman holding a water pitcher, pass the old cathedral a little further up, and arrive at the Castro, which proves to be extraordinary.

It sits on top of roman ruins: a labyrinth of, for lack of better words, interconnected archways built into the side of the steep hill to enable a forum and other structures to be built above them, where no flat ground existed previously. This labrynth is called the Aeminium Cryptoporticus (two levels of vaulted galleries, one on top of the other, to form the flat ground underneath the ancient city’s forum. Quite the engineering feat).

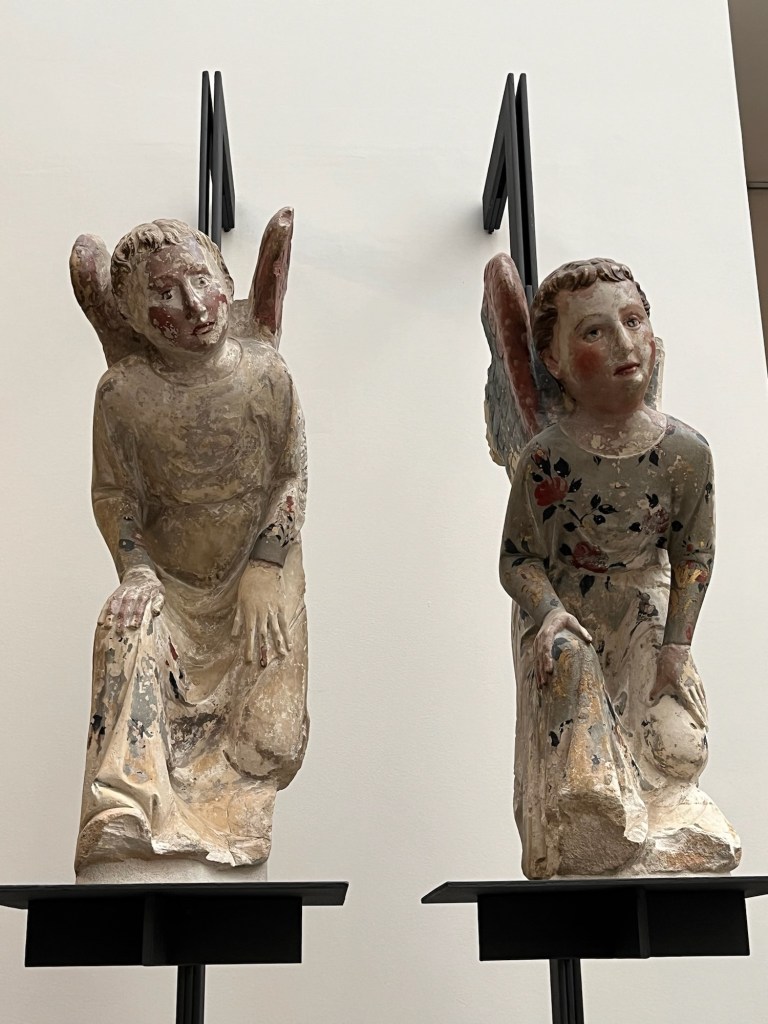

We all know what ultimately happened to the Romans. So, time passes and by the end of the 13th century, Coimbra has become the center of Portuguese sculpture and quite a hub for innovation in arts of all sorts, lasting until the middle of the 17th century. The stuff in the museum — sculpture from the local limestone, paintings and larger-than-life crucifixes and alter pieces, monstrances (a vessel for displaying an object of piety on an alter, often emanating holy rays from a clear circle), reliquaries, rugs, and all manner of interesting artifacts.

We stop off near the bronze gal on the “back down” and buy tickets for a fado performance the next night. We walk around the city a bit, savoring our first afternoon entirely without rain in about six or seven days.

Dinner is at a place known for its bacalau, which Cynthia tries again, and the recommended bottle of wine is … well … “Hemingwine,” to coin a new adjective … and trundle ourselves to the hotel.

Coimbra is lovely and we are grateful we came and especially happy that we got to see the Castro.